April 28, 2021

I have a lot of dreams about Hong Kong. Mostly nightmares. Variations on a theme.

The other night, I dreamed that I found myself back in my adopted home of Hong Kong again, walking on the familiar streets of central Hong Kong Island with friends.

I was immediately anxious. It wasn’t the nostalgic Hong Kong of my happiest memories I was in. It was still 2021, and Beijing’s National Security Law had already been implemented. Hong Kong was firmly a de-facto police state swarming with plainclothes and Mandarin-speaking riot police. I didn’t know how long I had been there, but I knew I needed to leave as soon as possible.

Before I could react, the next thing I knew we had been stopped by three jittery-eyed young policemen kitted-out in full riot gear and carrying submachineguns, their aura burning with blind intensity. They corralled us into an alley and demanded to see our Hong Kong IDs. My blood ran cold; I knew I would be arrested, and I had two or three guesses of what would happen after that. I had violated the new National Security Law by criticizing the Chinese state dozens of times after it was passed, meaning they would at least have an ostensibly legal justification to disappear me and do as they wished. Law or no law, I had been under some level of surveillance in the real world at least as early as June of 2019 after writing some articles about Huawei. I waited, defeated, under the hazy neon lights of the street signs above me as the young officer scrutinized his tablet. I was sure that my name and face would come up in their system, and that would be it.

They had any number of justifications under the newly established Chinese legal framework, and that’s all they’d need to arrest and disappear me into the grey jails within Hong Kong such as Pik Uk, where Amnesty International found conclusive evidence of torture — or worse, the opaque gulags of the Mainland under the guise of “following the course of justice in China“. I might have once been afforded special treatment as a foreigner in Hong Kong in 2018, but as I had been advised, those days were over. Would I mysteriously fall off a building like HKUST student Alex Chow Tsz Lok? Probably not. Held in a small windowless room in Beijing as a bartering piece? As the magic eight-ball would say, ‘all signs point to yes’. The officer with the tablet looked up and whispered something to his colleague.

The officer handed our IDs back, which I grabbed with a flood of relief. He told us to avoid meeting in groups and to stay home. I next found myself at the airport boarding a flight out of HK.

My own personal nightmare, at least, ended.

But I recently had another dream about Hong Kong. In it, I was surrounded by friends and students, old and new. The mood was festive and lighthearted as we talked and joked in Cantonese, ate noodles and other food in a market late into the night. We were in Hong Kong — but it was not the Hong Kong where I spent much of my adult life since 2011. I knew somehow it was another Hong Kong. It wasn’t just the buildings with neon signs, but the atmosphere: all the bustling streets and vivaciousness of Hong Kong, but without the oppression, “suicides”, and fear. A Hong Kong where Hongkongers could keep their culture alive and be optimistic for the future.

While Hong Kong’s neon lights and incredibly varied topography — city, mountains, towns, villages, forest, and ocean packed into just over 1100 square kilometers — are indeed some of the features that made Hong Kong so special, the dream made me realize that Hong Kong is much more than its physicality.

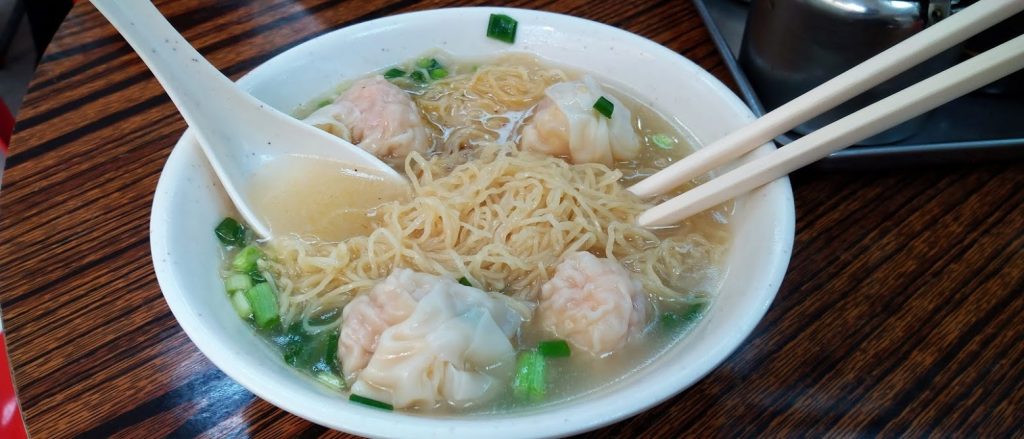

Hong Kong is hot and fresh wonton soup made from scratch, served by a smiling auntie who remembers your usual order. It’s hot milk tea and macaroni ham soup for breakfast. It’s cold beer and fresh seafood on the street with friends on a hot August night. It’s Cantonese slang and inside jokes; the way diu said just the right way says everything that needs to be said. It’s accidentally dropping a few hundred dollars (or even your whole wallet) in the middle of the most hectic rush hour and having multiple people chase after you to give it back. It’s long, quiet walks home at 4am after dancing the night away without a thought about safety.

Hong Kong is having the exhausted person next to you on the bus “go fishing” and fall asleep onto your shoulder, and you try not to wake them, because you understand their struggle. It’s how the tiny bar you frequent is a home away from home, and the owner looks after you like your own mother. It’s the way nearly two million people can protest with seemingly superhuman politeness. It’s the character of a people who have experienced so much change and hardship, who work 60 or more hours a week to make ends meet in one of the most competitive environments on Earth, yet still find the time to be warm and welcoming to you. To put one foot in front of the other and be decent, no matter what.

Hong Kong may be breathing its last breaths under the Chinese Communist Party, but the ethos of what it means to be a Hongkonger can’t be killed by physical oppression or by making ideas illegal. Police and military can occupy its streets, turn its school curriculum to propaganda, but Hongkongers are more hardy than that.

With new immigration pathways to Canada, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, more and more Hongkongers are leaving what was once their home and creating a new one. With any luck, the diaspora may reestablish vibrant communities, continue practicing their language and culture, and keep the character of Hongkongers alive.

Hong Kong isn’t a place; it’s a people.

Hong Kong is dead; long live Hong Kong.

Douglas Black is Writer for Pole Star Defense, Senior Editor, Lecturer, DJ, and music producer. He lived in China, Hong Kong, and other parts of Asia-Pacific from 2007-2019.